At age 90, Myrlie Evers-Williams has dedicated her life to the Civil Rights Movement in America, and along the way, she made the ultimate sacrifice: losing her husband, famed activist Medgar Evers, who was assassinated in June of 1963. Now, exactly 60 years later, the widow, mother and fearless freedom fighter opens up to PEOPLE in this week’s issue, reflecting on her incredible journey.

Myrlie Evers-Williams gazes wistfully at a photograph of Medgar Evers, the decorated Army veteran she married in 1951, when, at just 26, he was already a pioneering activist who would go on to challenge segregation and fight for the rights of Black Americans. “The best way I can describe it is he was the love of my life,” says Myrlie, now 90.

The photo is in a display case in a dimly lit basement room at Pomona College in Claremont, Calif., where Myrlie’s personal archives are stored. “I think I kept every scrap of paper,” she says. “I knew deep in my heart that everything my husband was doing and working for could be of use years later. He said, ‘Keep a record, Myrlie. History is one of the most important things we are going to have in life.’”

Mississippi Department of Archives and History

The couple themselves would soon become a key part of history, but not without devastating personal cost.

In the early morning of June 12, 1963, after years of working tirelessly as the NAACP’s first field secretary in Jackson, Miss., where he organized boycotts and protests alongside his wife to help expand the rights of Black Americans, Medgar was gunned down by a member of the Klu Klux Klan as he stood in the driveway outside his home. He was 37. Myrlie and their three young children were just inside.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Medgar’s assassination, one that helped crystallize the deadly toxicity of racism in this country and the desperate need for progress — and this month, the Everses are being honored in a Jackson celebration.

But for Myrlie — who’s spent the better part of her life taking up her husband’s torch and keeping his murder case in the forefront (Medgar’s murderer wasn’t convicted until 1994) — the painful memory of his assassination is still fresh. “If I could’ve taken those bullets that night, I would’ve,” she says. “I would have gladly given my life for his at any time, because I believed in him. Medgar taught me to be brave.”

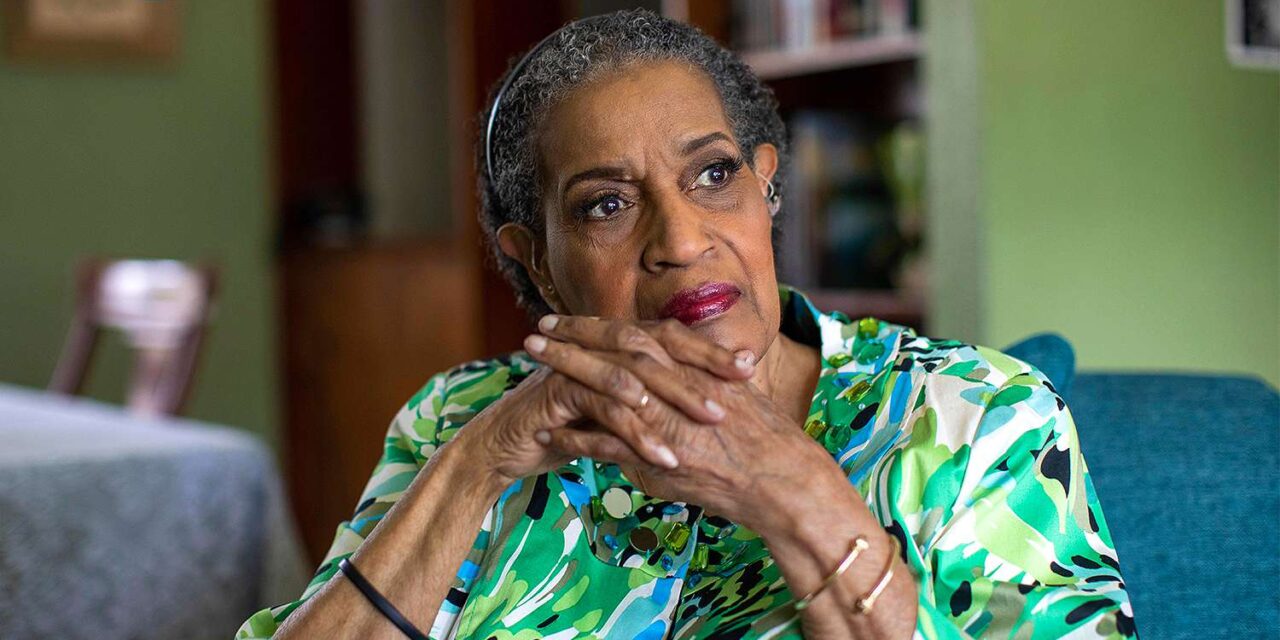

Tamika Moore

Raised in Mississippi, Myrlie was taught early on that courage could come at the ultimate price. “I was very familiar with all of the ills there,” she says. “You kept your mouth shut. I had no idea of what helping my people was before I met Medgar.”

The couple met while attending what is now Alcorn State University. “He was eight years older than me and a veteran. I was a sweet little 17-year-old. I was fascinated by his authority and the depth of his feeling.”

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer.

A friend of Martin Luther King Jr.’s, “Medgar put himself on the line when not many people did,” she says, “and it was frightening to me.” Still, she married and marched alongside him.

Medgar and Myrlie both knew the risk of the work they were doing in the Jim Crow South. “We’d receive threats all the time. There was one conversation where both of us were crying, and I told him, ‘I can’t make it alone.’ He said, ‘You’re stronger than you think.’ He finished by saying, ‘You take care of my children.’ It was an understanding we had.”

Corbis/Getty

Following her husband’s murder, Myrlie and their children — Darrell, who died in 2001 at age 47; Reena, 68; and James, 63 — were thrust into the spotlight.

“We were poor; we didn’t have anything, but people would bring meals, clothes for my children,” she recalls. “I found myself so thankful for those who supported me.”

She was also furious. Asked how she continued her activism after such a heinous act of violence was carried out on her family, she answers quickly: “Hate. I was full of it. I was determined to make whoever was responsible for my husband’s death pay.”

AP

It’s a truth she admits she’s not proud of, especially after dedicating her life to stamping out that very feeling. “I have been filled with so much anger in my life, I’m almost ashamed,” she says. “But I also realize I’m human.”

To get through, she says, “I repeated something on a regular basis that my grandmother used to say: ‘Baby, let go and let God.’ Without my faith, I don’t know who or where I would be.”

Tamika Moore

Myrlie relocated the family to California, where she resumed her studies at Pomona College. “That’s where I found myself again,” says Myrlie, who’d only completed two years of courses when Medgar was killed. “I knew it was necessary for me to have a degree to do a decent job supporting our kids.”

After earning a bachelor’s in sociology, she went on to become a journalist, businesswoman, author and two-time congressional candidate. But of all her jobs, “one of the toughest things I had to do was reinvigorate the NAACP.”

Getty

In the 1990s she became the preeminent voice of the organization, which was then in dire straits because of scandal and economic issues.

At the time, “The men [of the NAACP] said, ‘She can’t do anything, she’s just Medgar’s wife,’” Myrlie recalls. “I smiled and said, ‘Watch me.’”

Serving as chairperson, she helped reinstate the NAACP’s prestige and stability. And once again she found love amid the struggle. “My second husband was a prayer,” she says of Walter Edward Williams, an activist and one of the nation’s first Black longshoremen, whom she married in 1976.

John Storey/Getty

Williams was by her side on Feb. 5, 1994, when Byron De La Beckwith, who had evaded prison for decades after hung juries in two previous trials, was finally convicted and sentenced to life in prison for Medgar’s murder. (He died while still incarcerated at age 80 in 2001.)

“In marriage I’ve been twice blessed,” she says. It was Williams who encouraged her to keep fighting for justice “when almost everybody told me it would never happen.”

Williams died of prostate cancer one year after the verdict.

Tamika Moore

Now entering her 10th decade, Myrlie says, “I’m just beginning to feel a release from all the weight that’s been over me.” And yet there is more work to be done.

“When I look at the race situation today, I know that I have to keep going,” she says. “I’m tired, but I’m pretty strong. I can still kick.”

For more on Myrlie Evers’ inspiring life as a civil rights activist, subscribe now to PEOPLE or pick up this week’s issue, on newsstands Friday.